Welcome to the Charles Laughton section of the Hunts Cyclist

Website.

|

Charles Laughton as a raw recruit, wearing the round General

Service cap badge donned by those in the Training Reserve Battalions (picture as

seen in the 1987 Yorkshire TV documentary about Laughton, based in the book by

Simon Callow, who also hosted the programme, which was directed by

Nick Gray) |

|

The

name of this young soldier wearing the Huntingdonshire Regiment cap badge

is Charles Laughton. Laughton (Born Scarborough, Yorkshire, July 2nd 1899 -

Died Hollywood, California, December 15th 1962) is remembered worldwide as an

outstanding stage and film actor and director. Out of his distinguished acting

output, we could mention his characterizations as Doctor Moreau in "Island of

Lost Souls", the much-married Tudor king in "The Private Life of Henry

VIII", Javert in "Les Miserables", Captain Bligh in "Mutiny on

the Bounty", the Dutch painter in "Rembrandt", Quasimodo in "The

Hunchback of Notre-Dame", the timid schoolteacher in "This Land is Mine",

or barrister Sir Wilfrid Robarts in "Witness for the prosecution", just

to name a few among his many accomplished, and still unsurpassed, film roles.

Laughton is also celebrated for his only film as a director "The Night of the

Hunter", a haunting and genuinely poetic fable which stands out as one of

the most unique films in the story of world cinema. But back in 1917, when

Charles Laughton left his work at Claridges Hotel to join the army, little did

that young, stage-struck conscript imagine that what lied in store for him would

far surpass his youthful dreams of becoming an actor some day. |

| A bit of

background (1914-17) Laughton's parents owned the Pavilion hotel in Scarborough which, according to a

friend of the family (an officer posted to the headquarters of Yorkshire Coast

Defences during the Great War), was a place which military officers "(...)

made our house of call and none other than 'brass hats' frequented it"

(1).

It is quite possible that some officers of the Huntingdonshire Cyclists took

lodgings there as well. Scarborough had been the target of enemy fire in

December 16th 1914, when it was shelled, along with Whitby and Hartlepool, by

German battle cruisers. This prompted many soldiers being sent to the East coast

to reinforce the defences already there, like the 1/1st Bn. Huntingdonshire

Cyclists.

When Laughton left Stonyhurst College in 1915, his parents considered that, as

the eldest of their children, he was someday to take over the lead of the

business, and sent him to Claridges Hotel (London) to learn the trade from the

bottom up. Claridges, as many hotels during the war, had been depleted of a

sensible part of its personnel, as both foreign and British workers went to join

the armies of their respective countries (foreign personnel belonging to enemy

countries which did not leave at the beginning of the war eventually being

interned). Therefore, in a luxury hotel like Claridges, which badly needed

trained workers, the chance of employing a boy, still under military age, and

with sound hotel background must have been welcome. We should deduce that young

Charles was reasonably good in his work, as he eventually got a rise in his

salary. Still, it was not hoteldom he was passionate about, but theatre, and

accordingly, he spent his spare time and every available penny on what really

mattered to him: watching London shows from the pit and gallery, some of them

more than once (in fact, more than twice!). He would fondly remember plays like

Barrie's "A Kiss for Cinderella", and revues like "Razzle-Dazzle" and "Chu-Chin-Chow".

He idolized the West End stars, and particularly Gerald du Maurier, whose acting

greatly impressed him and who became his hero for the rest of his life. |

|

Into the Army

Laughton

joined the army in 1917, presumably shortly after his 18th birthday (one source

actually mentioning him joining in "summer 1917")

(2),

and it would seem that, at first, the release from hotel work was not unwelcome:

Laughton's mother would later state "His (hotel) training was interrupted by

the Great War. I think he was glad of thishappy not to have to be a waiter at

Claridges"(3)

(though we consider that he probably wasn't as happy about leaving

the West End theatre galleries behind).

Most recruits at the time received their early training in Training Reserve

Battalions. Charles' first steps, before joining the Huntingdonshire Cyclists,

were in the 87th Training Reserve Battalion at Catterick Camp, Yorkshire, where

L. Brayshaw was one of the training staff in the 87th T R B, and who would recall Laughton many years later: "I remember the

future film star visiting Catterick Camp as a recruit in 1917 or 1918 (...).

Laughton did not seem to be interested much in soldiering. We tried to show him

how to put on his puttees, but he never seemed able to manage to look smart in

them. After a few weeks infantry training, he was transferred to another unit.

That was the last I saw of him except, years later, in pictures"

(4).

Incidentally, by 1917, Catterick had a theatre run by the NACB (Navy and Army

Canteen Board.

(5)

Link - Charles Laughton - HCB

Notes.

We can tell that by February 1918 he was already in the Huntingdonshire

Cyclists, or, at least, this is the date mentioned in the 'Stonyhurst War

Record'. Laughton served in the 2/1st Battalion, D Company. At the beginning of

1917 the battalion was stationed in Sutton-le-Marsh, near Mablethorpe, moving to

Alford in March 1917, and then to Chapel St. Leonards in July 1917. In May 1918

the 2/1st Battalion would settle near Skegness.

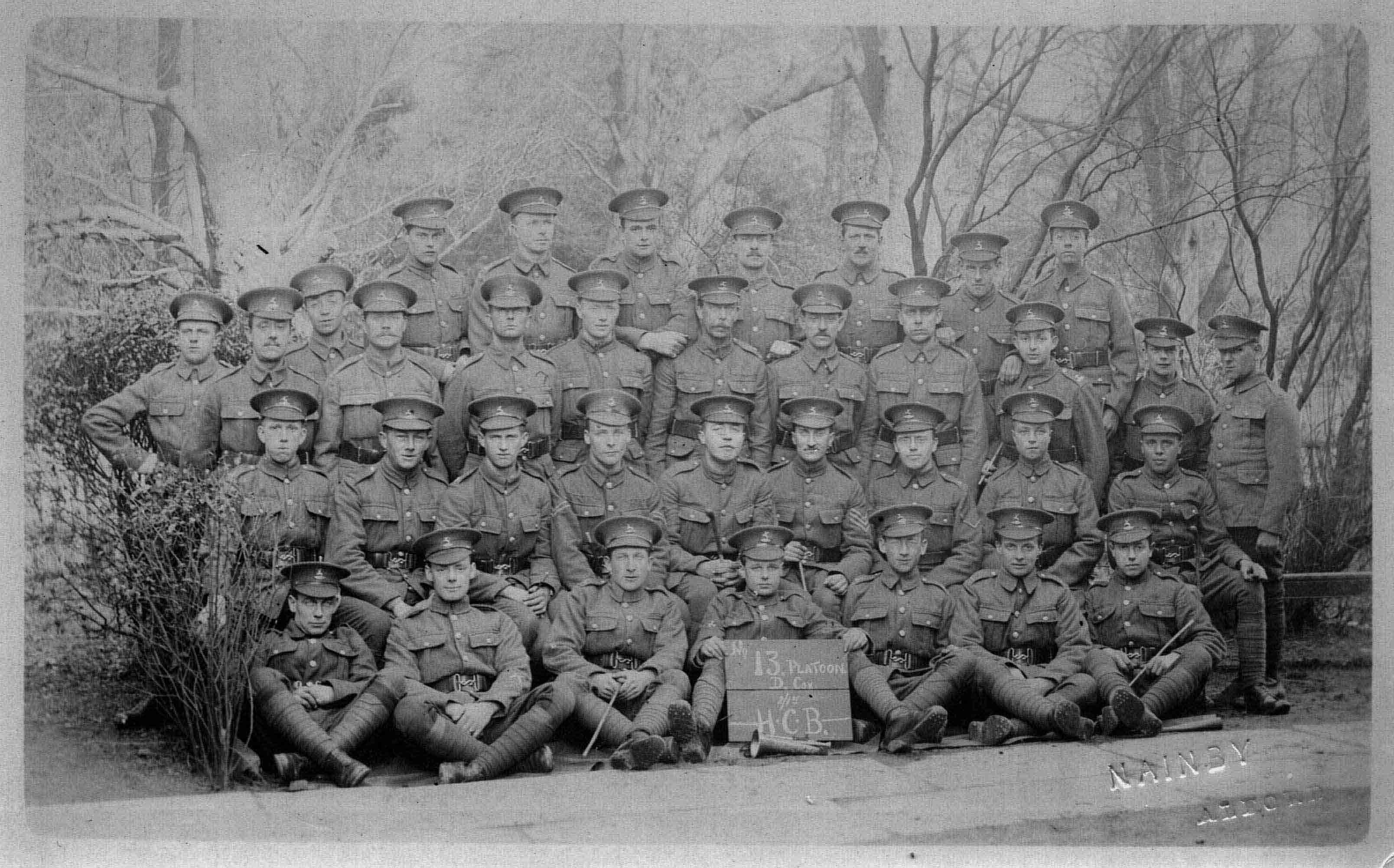

The grandson of Sergeant William Mould,

shared with us his family recollections: Mould was watching "Carry on Sergeant"

on TV (6),

and the film reminded him of the time when he had Laughton under his orders. We

believe that Laughton is the young soldier sitting by Sergeant Mould's side in a

group picture of the 13th Platoon, D Company 2/1st Battalion, Huntingdonshire

Cyclists (however, we can't be 100% sure of it as the soldiers appearing in the

photograph are not identified)

|

Photograph of the 13th Platoon 2/1st Hunts. Cyclist Battalion.

Date unknown - in print in photo is 'Nainby Alford' |

It is curious that these reminiscences seem to describe Laughton as the

archetypical clumsy soldier, as he was not inexperienced in military training:

he had been in the OTC of Stonyhurst College. Hence we dare to speculate if he

was not deliberately playing the part, and unknowingly rehearsing the part of

Good Soldier Schweick that many years later he would play in a riotous reading

of Bertolt Brecht's "Schweick in Second World War" for the author himself and a

few friends.

(7)

In the Stonyhurst OTC, which Charles would attend for two terms during his stay

at the school, his record as a cadet, if not outstanding, can safely be

described as average

(8). This begs the question why having had a Public School education

and OTC training, he enlisted as a private instead of joining an Officer Cadet

Battalion in order to try to obtain a commission as a junior officer. He would

explain the reasons years later: "Something told me I might not be the kind

of fellow to take command of men under fire, and so I stubbornly stood against

having a commission and was conscripted into the ranks"

(9).

|

|

|

This photo is of Charles

Laughton aged twelve, as he appeared in a 1912 photograph of a

group of Stonyhurst pupils. Laughton is wearing the Roman

Imperator medal he was awarded for Latin verse (This photo

appeared in the 2005 issue of "The Stonyhurst Magazine" by

courtesy of film historian Mr. Michael Burrows

Please follow this link to another Charles Laughton page where

this photograph can be compared to other group photos of people

who are thought possible to be Charles.

Please

follow this link to

another Charles

Laughton page

where this

photograph can be compared to other group photos of people who

are thought possible to be Charles.

|

Posted to

the Western Front

A couple

of sources

(10) mention that Laughton was in France by March 1918. However, while

trying to find evidence which might confirm this further, we will stick to the

notion that by this time he was employed in coastguard duties in Lincolnshire,

where he would remain until his nineteenth birthday, when he reached the minimal

age (11)

to be sent to the front. Along with 65 more men, he was struck off the strength

of the 2/1st Bn. Hunts Cyclists, and posted to France on August 9th, 1918.

Before being sent to the front, he was given a few days' leave (From 29th July

to 3rd August 1918 inclusive). The draft was conducted to France by Second

Lieutenants Cassidy and Cosgrave, who were back to Skegness on August 12th and

14th, respectively.

(12)

[See 'Drafts of

the 2/1st

Hunts Cyclists to France']

Laughton's entry in the WWI Medal Rolls, while not mentioning the

Huntingdonshire Cyclists (but then soldier's units in the UK were not

always mentioned there), names two units which were in France: the 4th

Battalion Bedfordshire Regiment (where he had the same regimental number

he had in the Huntingdonshire Regiment: 48603), and the 7th Bn.

Northamptonshire Regt. (with number 42603). He received both the Victory

Medal and the British War Medal, which were campaign medals generally

awarded to all those British soldiers who served overseas from 1916

onwards (only in some cases these medals would be forfeited, i.e. those

charged for desertion or cowardice)

Laughton's wife, Elsa Lanchester, would record in 1938 her husband's

reminiscences about having been sent "straight to the front"

(13),

which could suggest that his draft might have lost little time in base camps in

France, and was instead sorted quickly to units in need of reinforcements.

Whether he was initially meant to be posted to the 4th Bedford's, but eventually

redirected to the 7th Northants, or served with the 4th Bedford's for some time,

and then was transferred to the 7th Northants is still to be disclosed. However,

the war diaries of the battalions state that their brigades were in close touch

at the beginning of October 1918.

[See '4th (Reserve) Battalion

Beds Regiment']

[See7th Service Bat.

Northamptonshire Regt.']

At any event, it seems that he was in the 7th Northamptonshires for most

of his service in France: Laughton mentioned the following in a letter

to Mr. Edward Abbot, also a former soldier in the 7th Northants "I

certainly was in the 7th battalion Northamptonshire Regiment, and I do

remember I had to act as an interpreter for some days around

October-November 1918"

(14).

For those who might be surprised at the thought of Laughton being

employed occasionally as an interpreter, we must explain that he had

studied the French language from an early age (in a French nuns convent

in neighbouring Filey) and was known to speak it with a perfect accent,

so it is only logical that he could have put it to good use during the

war. Some years after, he would be the first English actor to act with

the famed Comédie Francaise, playing the part of Sganarelle in Moliere's

"Le Medecin Malgré Lui". As for other languages, at Stonyhurst he

had been a good student of Classics, and got prizes for Latin.

It is mentioned in some biographies that Laughton was at Vimy Ridge (the source

being his widow). For the data we have on Laughton's war service, we believe

this doesn't refer to the action in which the Ridge was taken, during the Battle

of Arras in Easter 1917, but to his being at, or near the place at some

undetermined point in 1918. From more general sources, we can only add that from

August 1918 to the armistice, the diary of the 4th Bedfords doesn't mention the

place, yet the 63rd Division (to which the 4th Bedfords belonged) was involved

in the Second Battles of Arras (which took place from the end of August to the

beginning of October 1918). It is also interesting to find that the 7th

Northants' diary states that the battalion was in and out of the Lens sector, a

few miles north of Vimy, from the end of August to the end of September

(incidentally, the 7th Northants had been involved in the battle of Vimy Ridge

assisting the Canadians the year before).

On his experiences at the front, he would state: "Being a 'softie' at the

time, I was naturally extremely frightened of what I was about to experience.

However, it did not take me very long to learn to do what I was told. Sometimes

it is a good thing for young people to have a complete change of environment at

an impressionable age. The War was more of an upheaval than a change. One

experience, which I would rather not talk about, took away my sleep

intermittently for two years afterwards, though looking back I admit the War

probably had a toughening effect on me" (15)

(To

discover more contemporary accounts of Laughton's experience in his own words,

check his

wartime letters.)

Further sources indicate that it was more than merely "a toughening

experience". His widow reported private comments of his guilt about having

made deadly use of the bayonet

(16), and even though this might have been done

either under orders or in the pressure of a "kill or get killed" situation, this

did not ease his feelings about it. At any event, the war experience was

instrumental in severing the Catholic faith in which he had been brought up.

There is a story reflecting this, repeated in different sources, of which we are

giving here the version reported by a good friend of Laughton, Davis Grubb

(17): "He had been a Catholic, an he told me about the time when he

was facing one of the bloodiest engagements of World War I. Laughton was in the

trenches, prepared to go over the top. It was some bridge, I think. (...) The

chaplain came through to give the Catholic soldiers absolution, and when he came

to Laughton, Laughton said, 'No thanks, father, I think I can take it from here

alone'. 'And' Laughton told me 'I never went back to church'"

(18).

Grubb also said that Laughton was disheartened about yet another World War

taking place. Probably, like many of the soldiers who fought in World War One,

he may have somehow have expected that his "big push" was the last ("The war to

end all wars", they called it). According to Davis Grubb, in Charles' opinion,

the Second World War "was a war we didn't really win. Nor, what's more, ever

shall (...) (and, as an ex-WW1 serviceman)...looked with a jaundiced eye

upon the 30,000,000 dead of his big show re-run. He didn't think we won either

war. He didn't think anybody ever wins a war"

(19).

Laughton would rarely speak about his experience, and never with much

detail. The following is an example of this: in 1940 Norman Corwin (the

outstanding writer and director, and also a friend of Laughton) wrote

and directed a radio play, "To Tim at Twenty"

(20),

about a soldier -played by Laughton- who writes a last letter to his son

as he departs for a doomed mission. Even though it was only a

fifteen-minute show, Laughton conscientiously rehearsed the part...

Corwin, with whom he worked hard to get the play right, was quite

surprised when I mentioned to him the fact that Laughton had fought in

the Western front: "(...) the remarkable thing to me about that phase

of his life, is that never once in all the years I knew him and worked

with him, did he ever mention the subject. Which is all the more

impressive when one considers that To Tim At Twenty is squarely on the

subject of war, and that the character he plays in it is a man about to

go on a mission from which he knows he will never return" (21)

|

| Gassed

After the defeat

suffered by the German army in August 8th 1918 (during the Battle of

Amiens) it became clear to the German High Command that the war couldn't

be won by military means, yet while diplomatic contacts may have been

conducted in high places, the war would go on for three more months.

Up to the very

last moment, soldiers fought, were wounded and died, and Laughton was

among these casualties, being gassed shortly before the armistice

(22).

He would later give the account to his friend and biographer Bruce

Zortman, of how he remembered "being gassed till my trachea bled and

my back oozed puss"

(23),

which describes well the caustic, burning effects of mustard gas, which

provoked large blisters on the exposed skin.

(More details about

chemical warfare.)

One of the consequences of his being gassed were allergic skin reactions all

through his life. The other was the characteristic husky voice for which he was

known in his early days on stage. In these early years he suffered from sore

throats quite often, and this almost put an end to his acting career until, in

1930, a specialist suggested that he should have throat surgery (tonsillectomy)

or else... This eventually worked well and, thankfully, Laughton's frequent

throat ailments became a thing of the past. |

|

Stage-struck at Lille

Maybe

still convalescing from the effects of gas

(24) Laughton had, "a month or so after the war

was over"

(25) an experience that in a way made up for the rough experience of

the fighting: "I saw Leslie Henson play in a pantomime in Lille- it was

'Aladdin'. He was damned funny as usual"

(26). The pantomime did more than merely cheer up the

wounded soldier: its effect was most inspiring as "the performance kept alive

my latent ambition (to become an actor)"

(27).

We don't know the exact date when he saw the performance, but you will

find

reference here

of "Aladdin" being played in Christmas 1918. Also, an entry dated December 31st

1918 in the War Diary of the 73rd brigade

(28) (to which the 7th Northants belonged), states

that the "BGC (Brigade General Commanding) attended a Pantomime in

Lille"... It's possible that the BGC went to see the show accompanied by

some members of his staff (and one speculates whether a certain private with

French language skills, as an occasional interpreter, might have managed to slip

into the expedition).

Laughton produced a film in 1938, "St. Martin's Lane", whose story deals

with the street entertainers (buskers) performing in the streets of the West

End. The film opens with documentary shots of the facades of some London

theatres: one of the light signs above the marquees advertises a show starring

Leslie Henson... Mere documentary coincidence? or the heartfelt homage of one

entertainer to another? |

|

Demobilization

Laughton left the army

in February 14th 1919, Along with other 7 rankers of the 7th Bn.

Norhamptonshire Regt. He was demobilized in the "Class Z" Reserve, which

meant that, had the hostilities been resumed after the armistice, he

would have been called up to rejoin the army. However, this did not

happen, and Laughton went back to work in the family business.

Re-adjustment to civilian life was not easy, though: Simon Callow's

biography states that, for over six months after his return from France,

" the boy that was remembered by everyone at home as being lively and

fun would lock himself in his room for hours on end. He said 'I'm no use

to anyone like this' "

(29)

. Anyway, at

his father's somewhat blunt prompting, he took his place as manager of

the hotel, while spending his spare time in amateur theatrical groups in

Scarborough. Tom Laughton would write that, after the war, the only

thing that made his brother Charles really come back to life was his

work in the amateur stage.(30)

No doubt Charles Laughton paid his dues to the theatre. Ten years later after

his demobilization, he would be wearing the uniform again... onstage: he was

playing Harry Heegan (31) in Sean O'Casey's world premiere of his war play "The Silver

Tassie", in the West End. The rest, as the saying goes, is history. |

| Further

information:

You can read

letters sent home by Laughton in 1917 and 1918 here

(link to letters

page)

You can read the

whereabouts of the 4th Bn. Bedfordshire Regt. here

(link to 4th

Bedfords page)

You can read the

whereabouts of the 7th Bn. Northamptonshire Regt. here

(link to 7th

Northants page)

You can read a text

about Leslie Henson and the Lille Theatre here, taken from the

book "Theatre at War 1914-18" by L. J. Collins, plus further bibliography and

links on Henson (link to Leslie Henson Page)

Learn here about

John Dermot MacSherry, Laughton's class-mate in Stonyhurst, who showed great

promise as an actor in the school's plays.

(link to MacSherry's Page)

Here you will find

more information and links about chemical warfare, and see a diagram of a

centre to deal with poison gas casualties for the Field Ambulance behind

Charles' Battalion.

(link to gas centre Page)

You can read more

information on Class Z demobilization

|

|

Notes and

sources:

1:

Mr. Crossley St. J. Broadbent,

quoted by Elsa Lanchester (Laughton's wife) in her 1938 book "Charles Laughton

And I". Faber and Faber, London. All Rights Reserved.

2:

Mr. Arthur Knight, in his profile

of Laughton (programme for the Charles Laughton film season at the Boston Museum

of Fine Arts, Fall 1972) gives this date, stating that he was gassed "the

following March (1918) during a German attack". The source is most

probably Elsa Lanchester (whom Mr. Deac Rossell interviews in another section of

the programme), so her memories could be inaccurate... Still it is interesting

to know that in another article about Laughton (published in 1949) it is

mentioned that he "served during the German breakthrough", though we

would prefer this to be further substantiated by primary sources. It is worth

noting that a letter -dated 19th September 1917- sent by Laughton to Miss

Thompson, the Pavilion's receptionist, described circumstances which suggest

outdoor life and frequent moves

(check Laughton's wartime letters

in

wartime letters.)

Sources:

"Charles Laughton, a man of many parts": texts written by William Lillys,

Arthur Knight and Deac Rossell, plus an interview with Elsa Lanchester. Boston

Museum of Fine arts, Fall 1972. Article in "The Leader" magazine, January

26th 1949. Both publications in the British Film Institute's Library. Letters

from Charles Laughton to Hepsebiah Thompson, copies of which are kept by Mr.

Simon Callow.

3:

Interview by

Stefan Lorant with Eliza Laughton in "To-day" June 4th, 1938 (Mander and

Mitchenson Collection, Jerwood Library).

4:

From Mr. L.

Brayshaw's letter published in "The Dalesman", October 1973, page 529.

(Scarborough Public Library)

5:

Mentioned by L. J. Collins in his

book "Theatre at War 1914-18" Jade Publishing Ltd., 2004 © L. J. Collins 2004

6:

"Carry On Sergeant"

was one of the first British comedies of the

"Carry On" series (not to be confused with the 1928 film of the same

title directed by Bruce Bairnsfather). It tells the story of a sergeant

desperately trying to make good soldiers out of a group of reluctant National

Service recruits, so Mould may have found a parallel with his own experience of

drilling conscripts like young Laughton.

7:

The character of Good Soldier

Schweick was created by Jaroslaw Hasek in 1911, and would be the central figure

of many short stories, later published in book form. It is the humorous story of

a Czech soldier in the Austro-Hungarian army, apparently an garrulous idiot,

whose naiveté and simplicity put to the test the military and bureaucratic

establishments of the Empire. Schweick exemplifies the little man who gets

caught in big circumstances, and somehow manages to get out of the grind.

Bertolt Brecht would re-take the character in his play "Schweick in the

Second World War", a wild satire against the Third Reich. Concerning the

occasion in which Laughton read the play to him, Brecht wrote " We laughed

uproariously. He got all the jokes", however, this play was discarded

and both actor and writer would finally settle for a production of "Life of

Galileo" (in whose translation-adaptation they worked together), which was

staged in Los Angeles and New York in 1947. Sources: "Charles Laughton. A difficult Actor" By Simon

Callow. Methuen London Ltd., 1987 © Simon Callow 1987. "Bertolt Brecht in

America" By James K. Lyon . Methuen London Ltd., 1982 © 1980 by Princeton

Press.

8:

While remaining a humble cadet throughout his stay at the

Stonyhurst OTC, this was not unusual among most other students there. If we take

the other twelve students which appear in his page at the OTC book as a sample,

we can see that his "efficiency" is described as good and his musketry "Second

Class", as six other cadets; the rest comprising five First Class shots, one

third class, and one who didn't practice musketry). Only one cadet out of the

thirteen in the page attended camp, though it must be said that he was a pre-war

cadet. As other cadets at the time, Charles got an OTC Discharge Certificate

upon leaving Stonyhurst.

In peacetime, an OTC cadet had to pass his examination for the "A" Certificate

("B" certificate if in an University OTC) to be a suitable candidate for a

commission. None of the cadets in Charles' page are noted as having an "A"

Certificate, however, As Mr. Charles Messenger states in the very thorough

chapter his book "Call to Arms" devoted to officer selection and training

"In November 1914, under War Office Instruction No. 22, Examinations for

Certificates A and B were suspended for the duration of war". This was due

to the growing need for subalterns as the the British army was steadily

expanding its size.

After February 1916 it was established that only men over the age of eighteen

and a half years with either OTC training or fighting experience in the ranks

would be admitted in Officer Cadet Battalions. Only those who had passed through

an OCB would be granted temporary commissions (excepting those who had already

served as officers).

Sources: Stonyhurst College's Archives. The background

information about OTCs and Commissions during First World War comes from Charles

Messenger's "Call To Arms. The British Army 1914-18" published in 2005 by

Cassell, a division of The Orion Publishing Group (London), ©Charles Messenger

2005, and "British Regiments 1914-18" By E. A. James © 2001 Naval And

Military Press Ltd

9:

Laughton quoted

by Elsa Lanchester. Lanchester, op. cit.

10:

See note 2

11:

In theory,

regulations prevented men from being sent to the front under the age of

nineteen, however this was not to be always the case: at the beginning of the

war, cases where boys joined after lying about their ages were not uncommon.

With the advent of conscription in 1916, this was more controlled. Yet, on

occasions of lack of manpower at the front, such as the one caused by the German

Spring attack of 1918, boys under this age were sent to the front as well... So

the rule was not strictly kept.

12:

Battalion

Orders of the 2/1st Battalion, Huntingdonshire Cyclist Regiment from June 30th

to September 28th 1918.

13:

Elsa

Lanchester, op. cit.

14:

Extracts from

the letters sent by Laughton to Edward Abbot. These were published in an article

in the Northamptonshire Regt. Newsletter no. 26 (May 1982). The letters were at

the time of publication in possession of Mr. Abbott's son, C. W. Abbot, whom we

are trying to locate.

15:

Elsa Lanchester, op.cit.

16:

Mentioned by Miss Lanchester in

her autobiography "Elsa Lanchester, Herself" (Michael Joseph Limited,

London, 1983. © Elsa Lanchester 1983), written after Laughton's death.

17:

Davis Grubb,

writer, was the author of the novel "The Night of the Hunter", whose film

adaptation Laughton directed in 1954.

18:

Davis Grubb as

quoted in Preston Neal Jones' book "Heaven And Hell To Play With"

(Limelight Editions, New York, 2002. © Preston Neal Jones 2002)

19:

Davis Grubb as

quoted in Jones, op. cit.

20:

The show was broadcasted on August 26th,

1940. Corwin's is a poignant story about the turmoil of war and how it disturbs

the lives of ordinary people, i.e.: keeping a father from seeing his son growing

up.

21:

Elsa Lanchester

also played a part in the play (as the soldier's wife), and they both rehearsed

at their home, as Corwin, who was writing for a film studio, was staying with

them as a guest. Mr. Corwin reported to me that they were both "conscientious

in rehearsal" even though "that particular programme (...)was short, very

short. It was only fifteen minutes". About the background which prompted him

to write it, he said:" This particular programme was written at a time when

the Luftwaffe was bombing London by the hundreds, and even the invasion of

England looked as though it might occur. And the Laughtons were almost daily

receiving news of casualties among their friends and relatives at home, and it

was no easy task for them to undertake a script of this kind, and they gave a

superb performance, unlikely to be equalled very often within so short a compass

of acting time" . Mr. Corwin defines the protagonist, Eric Marshall, as

"a thinking man" who "relishes neither the 'special work' he has to do,

nor the idea of being 'gone quite some time' which is euphemism for forever"

and who has a "slightly uncomfortable feeling that he and all the other

people who must die for the blunders of stupid and reckless statesmen are idiots

themselves for not getting together and putting, as he says 'a quick stop to the

nonsense' ", and that he wanted to convey to the listeners a message of

"Hope, not Triumph"

Sources: "Thirteen by Corwin" Radio Plays of Norman Corwin,

with preface of Carl Van Doren. Henry Holt and Company, New York and San

Francisco, 1942 © Norman Corwin, 1942. Interview with Mr Norman Corwin

(Gloria Porta, August 2004) and further correspondence.

22:

The statement comes from the 1938

book by Elsa Lanchester's 1938 book (op. cit.), written while Laughton was

alive, so this comes straight from him, and that's why we stick to this period

over the one mentioned in the source mentioned in note 2 (unless he had been

gassed twice, poor chap). Some other sources give the reference "one week

before armistice"... though these personal -or family- remembrances are not

always accurate, it is interesting to point that one week before armistice, in

November 4th 1918, the 7th Northamptonshires were involved in heavy fighting

over the terrain of the villages of Wargniers-le-Grand and Wargniers-le-Petit,

one of the actions consisting in crossing a bridge over the River Aunelle which

carried the Enlain-Bavay road which separated both Wargniers. The bridge was

defended by German machine guns.

23:

As recalled by

Mr. Bruce Zortman and mentioned to me. Mr. Zortman had previously collaborated

with Laughton in the preparation of the literary anthology "The Fabulous

Country" (McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1962), doing the extensive literary

research required. Being very satisfied with Zortman's work, Laughton asked him

to assist him in writing his autobiography. Laughton's final illness and death

in 1962 sadly kept the work from being finished.

24:

On these dates,

the 7th Bn. Northamptonshire Regt. was in Bachy, and later in Tournai. The war

diary of the Battalion doesn't mention the unit, or any of its personnel being

at Lille or attending a show around these dates, so if Laughton was in Lille it

must have been on some sort of leave (or on an errand?), convalescing or

otherwise. Still, see further comment in the paragraph from the Brigade diary.

25:

Interview to

Charles Laughton by Patrick Murphy, Sunday Express, p. 9, London November 19th

1933. British Library Newspapers.

26: Elsa

Lanchester, op.cit.

27:

Interview to

Charles Laughton by Patrick Murphy, Sunday Express, p. 9, London November 19th

1933. British Library Newspapers.

28:

War diary of

the 73rd Brigade, Ref. WO 95/2217. National Archives, London

29:

Simon Callow,

op. cit.

30:

Mentioned by Tom Laughton in his

book "Pavilions By The Sea", Chatto and Windus Ltd. 1977 © Tom Laughton 1977

31:

Harry Heegan is the tragic hero of "The Silver Tassie", an Irish

footballer maimed in the war, confined to a wheelchair, and subsequently left

aside by those who had previously cheered him. Sean O'Casey modelled Heegan

after a real-life character. Contemporary reviews more or less agreed that,

while Laughton seemed physically unsuited to play the athlete of Act I, he

harrowingly captured the essence of the tragedy of war as he played the crippled

Harry in Acts III and IV. Laughton also played the First Soldier in the second

act. |

|

Acknowledgements

As

anyone who has done research on Great War subjects will tell you, tracing the

whereabouts of a ranker during that period can prove a difficult task, therefore

we are extremely grateful to all the people who have helped us along the way. We

are grateful to the authors, publishers and archives who have allowed use of

material for the elaboration of this article. Every effort has been made to

trace copyright owners for the use of materials. If any errors or omissions have

accidentally occurred they will be corrected in subsequent updates of this

website.

The following individuals and institutions have been instrumental in helping us

find information about Charles Laughton during that period of his life: The

British Library, Simon Callow, Norman Corwin, Oliver Furnell, Mr. David Knight

(Stonyhurst College archivist), The Mander and Mitchenson Collection (Jerwood

Library), Preston Neal Jones, Scarborough Public Library, Theatre Museum, Bruce

Zortman.

I'd like to thank further Mr. David Knight for his English corrections of

earlier drafts of these articles.

We have not been able to trace the whereabouts of the relatives of Mr. Edward

Abbot, Mr. L. Brayshaw, Major Geoffrey Moore and Ms. Hepzebiah Thompson, but

they are to be thanked as well as their remembrances, written articles and

personal letters have helped in shedding light on Charles Laughton's war

service.

Of course, when researching any individual, it is important to place him/her

within his/her historical circumstances, so we would like to thank Col. Terry

Cave and Mr. Norman Holding for their help and information about the British

army during First World War (and how to research it), and also many members of

the Great War Forum who have given helpful hints and bits of information. We

would also like to thank the Huntingdon Record Office, The Peterborough Record

Office and the Peterborough Library for their assistance in our research of

sources relating the Huntingdonshire Cyclist Regiment. We would also like to

thank Ms. Susan Scott, Archivist of The Savoy Group, for her background

information on Claridges Hotel during wartime; Mr. Steve Fuller, Mr. Nigel Lutt

and the Bedfordshire County Record Office, Mr. Barry Stephenson and the Bedford

Central Library, and Mr. John Wainwright for their help and information about

the 4th Battalion Bedfordshire Regiment; Mr. Doug Lewis for his information of

casualties of the 7th battalion, Northamptonshire Regiment, Dr Larry J. Collins

for allowing us to quote paragraphs of his book "Theatre at War 1914-18". The

National Archives, for keeping War Diaries, Divisional diaries, Medal Rolls and

other documents which have been of primal importance for this research

(unfortunately, they don't keep Laughton's War Record as it was one of the 70%

or so Great War records lost by fire causes by Luftwaffe bombings during Second

World War). The Library and Archives Canada for

kindly allowing use of an image in their collections

At some points, we have added links to external websites in order to give

further information on some of the issues dealt with in these articles. We would

like to thank the webmasters and/or owners of these sites for giving us

permission to do so: Mr. Chris Baker, Mr. Michael D'Alessandro, Mr. Steve

Fuller, the Imperial War Museum, Mr. A Langley, Ms. Esther MacCallum-Stewart,

Mr. Geoffrey Miller, Mr. Joe Sweeney and Mr. Johan Somers.

Mr. Rob Ruggenberg (from "The Great War heritage"), Ms. Natasha Wallace (from

jssgallery.org), Mr. Howard Anderson (of the Western Front Association Website),

Michael Duffy (from firstworldwar.com), the BBC History Website. |

|

05/12/2017. |

Most of the data on this page has very kindly been provided by Gloria

Porta - many thanks to her and to all those mentioned for permission to

use their information and research. Where possible all credit has

been given to them and the original source quoted. |